Raycast Obstacle Avoidance

A couple of months back, I stumbled upon this gif while surfing Dribble. It was mesmerizing, seeing these little dudes weave in and out of these squares and leaving smoke trails behind them – as if they were skiing down a mountain between the pine trees. After some sleuthing, I found the source – this article. Lo and behold, it was actual AI for a game, and not just some animation created in Flash. Around this time, I had a project coming up for AI: to research a topic that wasn’t presented in class, and to create a tech demo to display my understanding. Down the rabbit hole I went, ray cast obstacle avoidance was my choice.

Before I get to showing my implementation and the inner workings of the algorithm, I want to first show just how important this is to the world of games. Ray casting has had a part in games for a while – lots of 2D lighting algorithms use ray casting to determine shadows, especially top down. Even 3D games and engines use a form of ray casting to determine what’s lit up by a torch and what lurks in the darkness. In more recent times, ray cast obstacle avoidance has been used for AI companions. Over a long trek, most games use one of the many forms of pathfinding to get from point A to point B, but when there’s an orc blocking the path, or an NPC crosses their path, rather than bump repeatedly into the object, they avoid the object, using a form of ray casting. Racing games use obstacle avoidance too – Mario Kart to get around items on the higher difficulty levels, and AI bots in AirBrawl use it to fly well enough not to crash into buildings. Overall, it is pretty useful when looking forward in the short-term. What’s great about it, too, is that it can be as computationally expensive or inexpensive as needed, which means it could run on virtually any platform in some capacity.

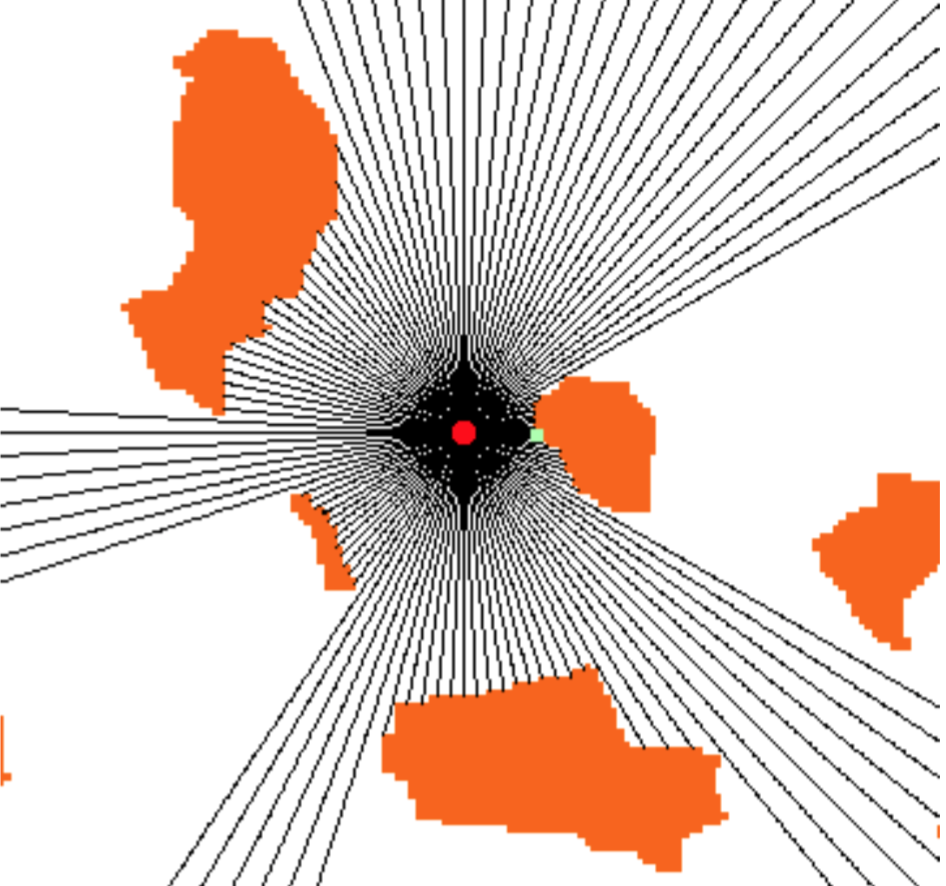

The idea at its core is pretty simple – points rays of some length in some direction, and react accordingly based on collisions with other objects. For instance, the above gif has five rays placed in front of it, the ones in the middle being longer. These then collide with the impeding blocks and moves the circle in the according direction. For this tech demo, I decided to try SpriteKit out on OS X, and I wanted to experiment and try to create new ways of using this method.

My implementation has three modes: a ‘plain jane’ of sorts, a follow/avoid behavior, and a shrinking behavior. Right now, the impulse that is applied is done so only once, when contact first begins between the ray and the object, but there are plenty of possible avenues of exploration. Things like letting the boid know the distance between it and the object, or its relative speed, or angle – things a human would be able to quickly recognize if something was flying at them. My tech demo allows for tweaking of the ray length, the angle of them, the force that is applied on the boid on contact, and the number of rocks flying at the boids.

More gifs, code snippets, and a link to a build will be made available over on my projects page. I’ll probably add it over winter break – finals crawl amongst the students.

Sources for research, gifs, and what not:

Next stop on the ray cast train.

Some interesting discussion for different AI algorithms in racing games.

AirBrawl’s implementation of obstacle avoidance.